How to distribute points on the surface of a sphere as evenly as possibly is an incredibly important problem in maths, science and computing, and mapping the Fibonacci lattice onto the surface of a sphere via equal-area projection is an extremely fast and effective approximate method to achieve this. I show that with only minor modifications it can be made even better.

First published: 10 August, 2018

Last modified: 7 June , 2020

***

This post has been superceded by the more recent post:

“How to evenly distribute points on a sphere more evenly than the canonical Fibonacci Lattice“

Please reference this newer link wherever possible.

This post has been kept as an archival record.

***

A while back, this post was featured on the front page of Hacker News. Visit here for discussion.

Introduction

The problem of how to evenly distribute points on a sphere has a very long history and is one of the most studied problems in the mathematical literature associated with spherical geometry. It is of critical importance in many areas of mathematics, physics, chemistry including numerical analysis, approximation theory, coding theory, crystallography, electrostatics, computer graphics, viral morphology to name just a few.

Unfortunately, with the exception of a few special cases (namely the platonic solids) it is not possible to exactly equally distribute points on the sphere. Furthermore, the solution to this problem is critically dependent on the criteria used to judge the uniformity. There are many criteria in use, and they include:

- Packing and covering

- Convex hulls, Voronoi cells and Delaunay triangles,

- Riesz

- Cubature and Determinants

Repeating this point as it is crucial: there is usually no single optimal solution to this question, because an optimal solution based on one criteria is often not an optimal point distribution for another. For example, in this post, we will also find that optimising for packing does not necessarily produce an optimal convex hull, and vice-versa.

For sake of brevity, this post focuses on just two of these: the minimum packing distance and convex hull / Delaunay mesh measures (volume and area).

Section 1 will show how we can modify the canonical Fibonacci lattice to consistently produce a tighter packing configuration.

Section 2 will show how we can modify the canonical Fibonacci lattice that produce larger convex hull measures (volume and surface area).

Section 1. Optimizing Packing Distance

This is often referred to as “Tammes’s problem” due to the botanist Tammes, who searched for an explanation of the surface structure of pollen grains. The packing criterion asks us to maximize the smallest neighboring distance among the

This value decreases at a rate ~

The Fibonacci Lattice

One very elegant solution is modeled after nodes appearing in nature such as the seed distribution on the head of a sunflower or a pine cone, a phenomenon known as spiral phyllotaxis. Coxeter demonstrated these arrangements are fundamentally related to the Fibonacci sequence,

There are two similar definitions of the spherical Fibonacci lattice point set in the literature. The original one is strictly only defined for

Whilst the second one generalises this to arbitrary

where

The spherical fibonacci spiral produced from equation 1, results in a value of

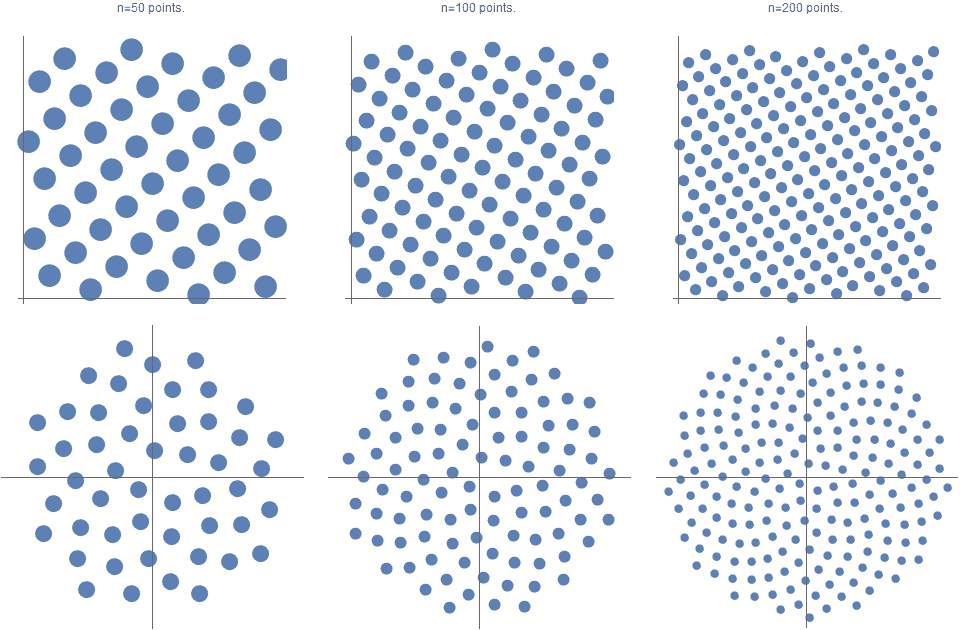

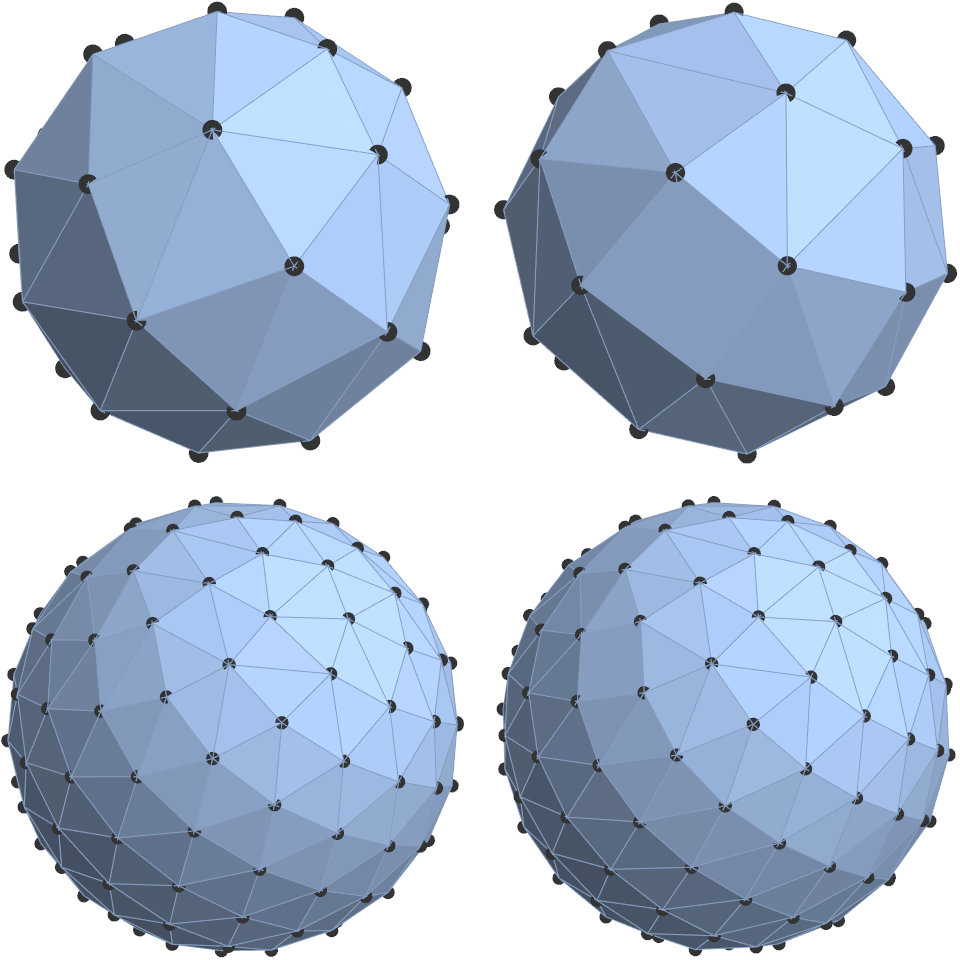

An example of these Fibonacci Grids is shown below. These points sets can be transformed to a well-known Fibonacci spirals via the transformation

Similarly, these point sets can be mapped from the unit square

Here’s a basic implementation of this in Python.

from numpy import arange, pi, sin, cos, arccos

n = 50

i = arange(0, n, dtype=float) + 0.5

phi = arccos(1 - 2*i/n)

goldenRatio = (1 + 5**0.5)/2

theta = 2 pi * i / goldenRatio

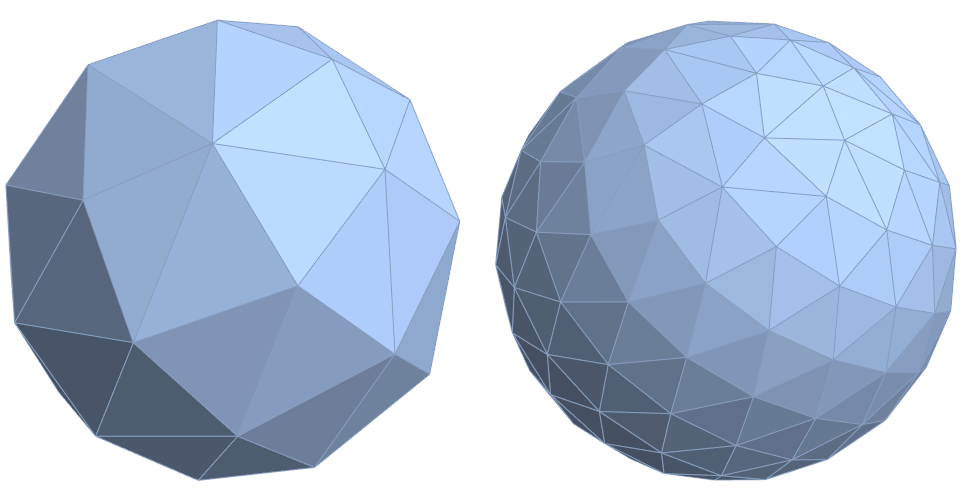

x, y, z = cos(theta) * sin(phi), sin(theta) * sin(phi), cos(phi);Even though spherical Fibonacci point sets are not the globally best distribution of samples on a sphere, (because their solutions do not coincide with the platonic solids for

As the mapping from the unit square to the surface of the sphere is done via an area-preserving projection, one can expect that if the original points are evenly distributed then they will also quite well evenly distributed on the sphere’s surface. However, this does not mean that it is provably optimal.

This mapping suffers from two distinct but inter-related problems.

The first is that this mapping is area-preserving, not distance preserving. Given that in our case, our objective constraint is maximizing the minimum pairwise distance separation between points, then it is not guaranteed that such distance-based constraints and relationships will hold after the projection.

The second, and from a pragmatic point of view possibly the trickiest to resolve, is that the mapping has a two singularity points at each pole. Consider two points very close to the pole but 180 degrees different in longitude. On the unit square, (and also on the cylindrical projection) they would correspond to two points that are quite distant from each other, and yet when mapped to the surface of the sphere they could be joined be a very small great arc going over the north pole. It is this particular issue that makes many of the spiral mappings sub-optimal.

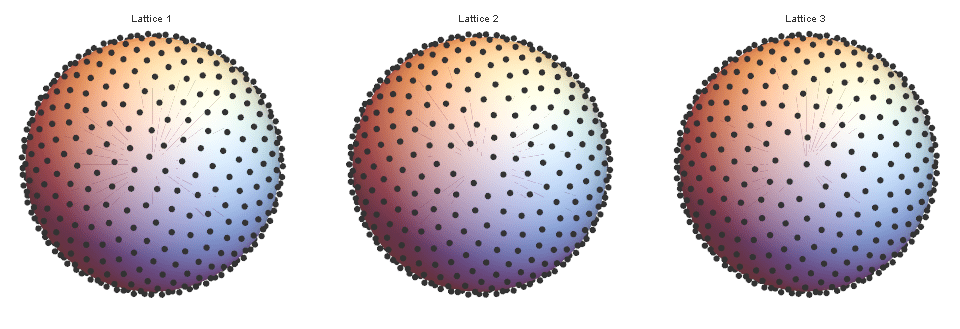

Lattice 1

A common variant, which produces a better packing (

It places the points in the midpoints of the intervals (aka the midpoint rule in gausssian quadrature), and so for

Lattice 2.

A key insight to further improving on Equation 2, is to realize that the

Let’s define the following distribution:

Note that

Based on this model, it can be shown that for

Thus for

Lattice 3.

As stated earlier, one of the greatest challenges of the distributing points evenly on the sphere is that the optimal distribution critically depends on which objective function you use. It turns out that local measures such as

In our case, regardless of how large

It is almost identical to lattice 2 but with two differences. Firstly, it uses

This lattice results in

Thus for

Comparison

For large

Here are the corresponding values of

And here are the corresponding values of

Also, the truncated icosahedron, which is the shape of a

Thus for

As per the first reference, some of the state-of-the-art methods which are typically complex and require recursive and/or dynamic programming are as follows (the higher the better).

Section 1 Summary

Lattice 3 (as defined in equation 4) produces a significantly tighter packing than the canonical Fibonacci lattice. That is,

Section 2. Optimising the Convex hull (Delaunay mesh)

Although the previous section optimized for

Let us define

where the normalization factor of

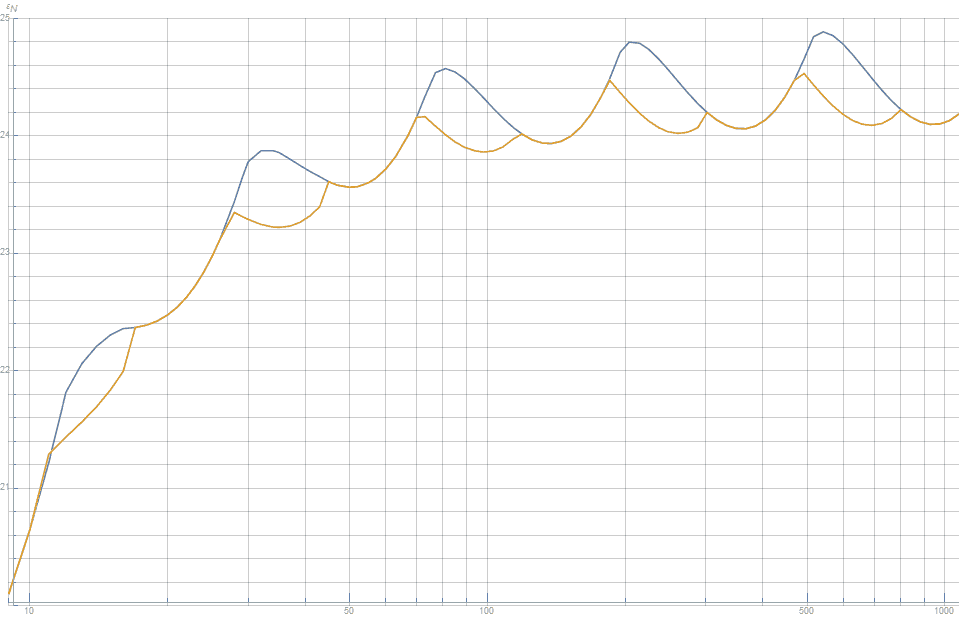

The behavior of

The key to improving the volume discrepancy is to note that although the use of

Thus, let us generalize equation 1 as follows:

where we define

where,

where

Figure 3 shows that this substantially improves the volume discrepancy for half the values of

The underlying reason why this works is based on the less well known fact that all numbers

And thus the connection why

For the remaining half, we first define an auxiliary sequence

That is,

The convergents of this sequence all have elegant continued fractions, and in the limit converge to

We now fully generalize

The following table is a summary of the value of

Figure 3 shows that, in relation to convex hull volume, this new distribution is better than the canonical lattice for all values of

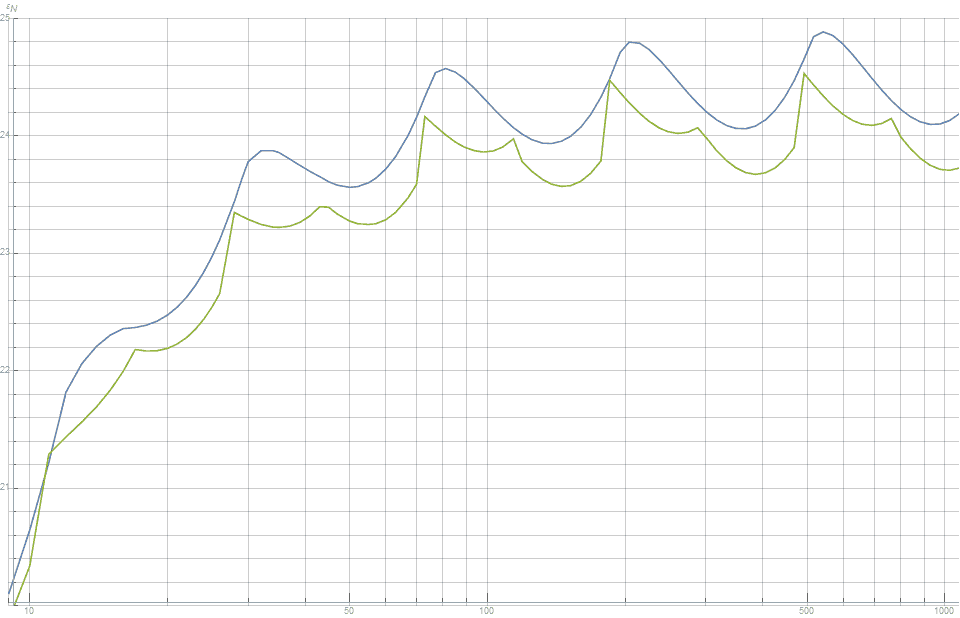

Figure 3. The discrepancy between the volume of the convex hull of points and the volume of a unit sphere. Note that smaller is better. This shows that the newly proposed method (green) produces consistently better distribution than the canonical Fibonacci lattice (blue).

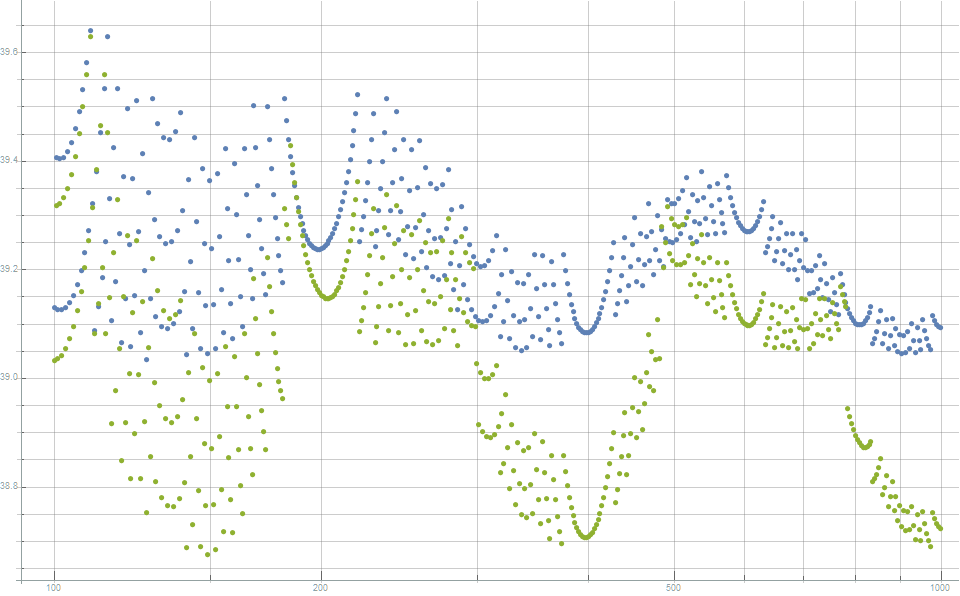

Of interest, this distribution also slightly but consistently reduces the discrepancy between the surface area of the convex hull and the surface area of the unit sphere. This is shown in figure 5.

Section 2 Summary

The lattice as per equation 6, is a modification of the canonical Fibonacci lattice that produces a significantly better point distribution as measured by the volume and surface area of the convex hull (Delaunay Mesh).

Key References

- A Comparison of poopular point confugrations on S^2“:

- http://web.archive.org/web/20120421191837/

- http://www.cgafaq.info/wiki/Evenly_distributed_points_on_sphere

- https://perswww.kuleuven.be/~u0017946/publications/Papers97/art97a-Saff-Kuijlaars-MI/Saff-Kuijlaars-MathIntel97.pdf

- https://projecteuclid.org/download/pdf_1/euclid.em/1067634731

- https://maths-people.anu.edu.au/~leopardi/Leopardi-Sphere-PhD-Thesis.pdf

- https://www.irit.fr/~David.Vanderhaeghe/M2IGAI-CO/2016-g1/docs/spherical_fibonacci_mapping.pdf

- https://arxiv.org/pdf/1407.8282.pdf

- https://maths-people.anu.edu.au/~leopardi/Macquarie-sphere-talk.pdf

***

My name is Dr Martin Roberts, and I’m a freelance Principal Data Science consultant, who loves working at the intersection of maths and computing.

“I transform and modernize organizations through innovative data strategies solutions.”You can contact me through any of these channels.

LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/martinroberts/

Twitter: @TechSparx https://twitter.com/TechSparx

email: Martin (at) RobertsAnalytics (dot) com

More details about me can be found here.

Other Posts you might like:

This is great stuff, thank you for sharing!

Something I think worth pointing out is that this “The packing criterion asks us to maximize the smallest neighboring distance among the points” is exactly what Mitchell’s best candidate algorithm does, so this seems to be blue noise distributed sampling points on a sphere, but without the need to do point generation in advance.

However, since it’s a low discrepancy sequence (golden ratio!) and not strictly blue noise, I bet it has (integration etc!) properties more like LDS, and less like blue noise. AFAIK blue noise is nice for visual patterns (perceptual error), but LDS is better for integration in general.

As a graphics person, I think it would be neat to explore the differences visually, for path tracing, calculating ambient occlusion, etc!

Great write-up. Very cool.

But the notation is a little unclear. Should eqn (4) have g(N) instead of g(n)? Or even g(i), perhaps? n is never defined. Likewise, I assume eqn (6) should have g(k).

Hi Nadav,

You’re right. They should have all been

Thanks.

I find your discussion confusing. In what sense does the set of points t_i live on the unit square? In other words, what is the mapping? It would help to label the sources of the grid points in a simple case. For example, should the point corresponding to t_0 be located at the origin in your polar grids?

Fascinating stuff. A question that still remains: Is there a better-than-canonical distribution that is also as smooth as, or smoother than, the canonical distribution? Figures 2, 3 and 5 show that the canonical lattice has a smooth distribution curve, and that the curve of the hybrid proposed model is not only jagged, but has twice as many up-and-down oscillations as the canonical lattice. Maybe there are other models that have 3 times as many oscillations, 4 times as many, 5, 6, 7, etc., and maybe those can all be infinitely summed up and averaged for a model that is both better and smoother than canonical?

Hi Gus,

After all the years I have spent trying to improve it, my conclusion is that any attempt to optimize for some particular objective will significantly compromise it another way. The parsimonious nature of the canonical lattice is incredible, and so although I will continue to be try to explore the edges of possibility, I think that we will not find a better model, that is as elegant as this canonical struture.

Here the Python code for distributing points evenly on a unit square:

import math

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

num_points = 100

golden_ratio = (1 + 5**0.5) / 2

xs = []

ys = []

for i in range(num_points):

x = i / num_points

y = i / golden_ratio

# fractional part!

y = y – math.floor(y)

xs.append(x)

ys.append(y)

plt.scatter(xs, ys)

plt.show()

It’s important to take the fractional part of the y-coordinate, what has been mentioned only in the follow-up post.

thanks for this.

How to distribute points evenly in a unit square is exactly what my main blog post is about!

I think you will enjoy it! : The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Quasirandom Sequences